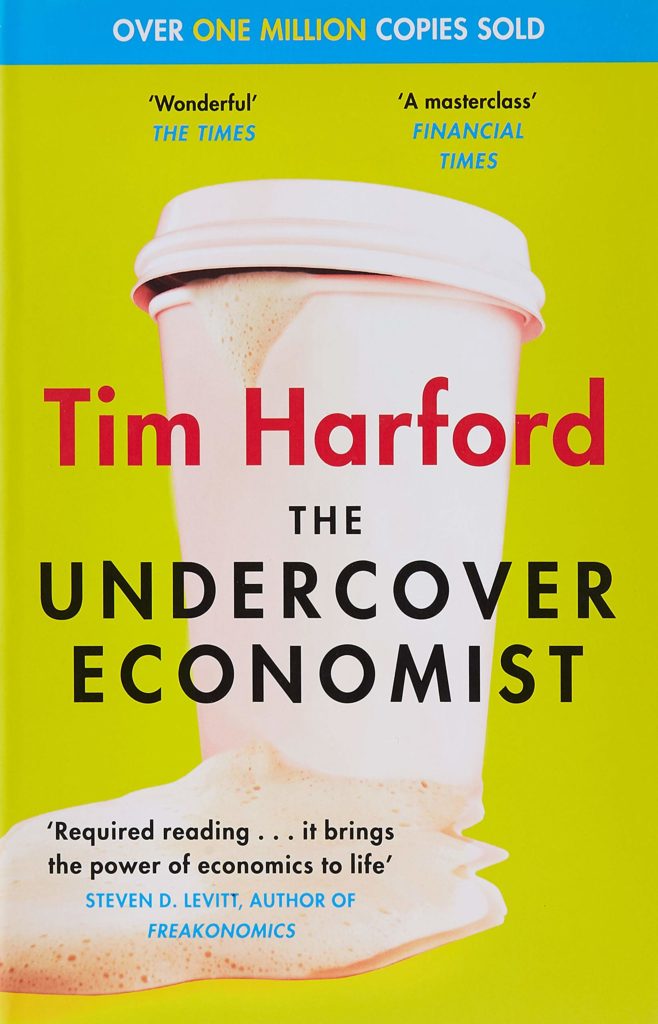

The Undercover Economist on how to manage your time and attention

The Business Magazine is always keen to showcase new thinking when it comes to tackling real world problems and that is why we have joined up with Label Ventures who last year published a collection of features on strategy, design and innovation under the FLIP banner.

Over the coming weeks and months we will publish a selection of entries from the FLIP book to share some of the innovative ideas contained within.

We would very much like to create a FLIP book full of creative thinking from the South East so if you think differently when it comes to the challenges of work or life and want to share your views then please do get in touch with me Stephen Emerson, head of content for The Business Magazine.

The first instalment features a piece by best-selling author The Undercover Economist Tim Harford who talks about how he manages his time and demands on his attention.

Tim Harford has a mind that is both brilliant and bustling. The Undercover Economist is a best-selling author who also presents Radio 4’s More or Less, the new Cautionary Tales podcast and the iTunes-topping Fifty Things That Made The Modern Economy. He is a senior columnist at the Financial Times, an award-winning speaker, an associate member of Nuffield College, Oxford and he has been awarded the OBE for services to improving economic understanding.

His latest book, How To Make The World Add Up, is already a Sunday Times best-seller. In this article, we share a conversation between Tim and Label Ventures’ Maxine Mackie, which delves into how Tim manages his time and the various demands on his attention, and how others can apply some of his observations in a work context as well as everyday life.

Maxine:

In one of the conversations I’ve been having for this magazine, a creative told me that it’s not the juggling of multiple projects at the same time that’s challenging; it’s all the communication from multiple projects at once. You’re someone who’s published many books, you have the podcast Cautionary Tales, a radio show and a Financial Times column. How do you manage the many things that you do?

Tim:

Part of the issue is that we tend to rely on email as a communication channel, and alternative apps such as Slack and WhatsApp still don’t solve the basic problem of constantly trying to coordinate projects on an ad-hoc basis. Because you’re doing that, you constantly have to check your email, and your email contains all kinds of other distractions. There’s that continual feeling of nervous energy and distraction. The idea I’ve discussed in some of my writing and in my books – slow motion multi-tasking – is based on the fact that it is good for you to have multiple ideas and multiple projects… one of the reasons I talk about that is to make myself feel better! People like Einstein and Darwin did their work long before email came along, and I don’t think I’ve solved this particular means of communication. Email is still there as a constant distraction.

Maxine:

I also think there’s an issue with the notifications. One thing I do is to turn them off for a period of time and then come back, so I’m organising my time that way. Because, otherwise, there are all these things coming at you all of the time.

Tim:

One strategy I have is to say that I’m going to take a virtual aeroplane trip, because people are familiar with how you can get so much done when you’re on a flight. I once did a whole book proposal on a flight. So, one way to replicate that is to just say to yourself that today you’re going to switch off your internet connection between 9am and 3pm as if you were on a long haul flight. And when people ask why you haven’t responded to their email you can say, ‘I was on a plane.’ It’s perfectly possible to do that. I think we have to use these tools and tricks in order to focus our attention.

Maxine:

Can you tell me a little about your book, How To Make The World Add Up, and what made you decide to write it?

Tim:

There’s some very interesting research that suggests disinformation spreads partly because people are clicking and sharing things without necessarily stopping to think. So the book is about making sense of things by being wise about statistics, and giving people some confidence to ask questions about the statistics that they see all around them to identify where there may be biases. I’ve become dissatisfied with the way a lot of popular books use statistics in a very outdated way. They generalise, which leads to cynicism and scepticism. Indiscriminate disbelief is no better than indiscriminate belief.

We tend to focus on the crazy things some people believe, but I think it’s more insightful to focus on what causes people to stop believing – in science, in institutions, in data. I think a lot of conspiracy thinking is best understood first as a process, rather than just indiscriminate disbelief. I wanted to write a book that was a bit more positive, to say that it is actually possible to discern the truth. That’s very useful, not just for fighting disinformation. And the other thing I wanted to do was to give the book psychological realism, to remind people that a lot of what we believe or disbelieve is because of our own preconceptions and tribal loyalties, and to try to be somewhat insightful about that.

Maxine:

I’ve been listening to a podcast about music Dissect, and each episode spends 30 minutes analysing an album. There’s just one guy making it, and he says that it takes about 20 hours to put together one 30 minute episode, and he’s doing that for 10 to 15 episodes. I was curious about how you approach research. How do you decide when you’ve done enough?

Tim:

Something I did in the recent series of Cautionary Tales is revisit people in my book, like Twyla Tharp and Florence Nightingale. I’ve been astonished at how much I missed the first time around. You think you’ve researched something over and over again and then you try to tell it and make sure every word you use is accurate and you’ve got all the interesting stuff. So, to come back a few months later or – in some cases – a decade later, to the same story, the same background and to be astonished at how much you didn’t see… you simply can’t believe it. I don’t know what the lesson is from that, but I suppose what a paid designer would think is that if you approach a problem from a different direction with a fresh perspective, you see different things. Imagining a dialogue and actors rather than writing a book – they don’t seem very different in terms of my process. But in terms of the audience, you learn different things even by approaching from a similar angle.

We’re constantly being interrupted. One thing I find useful, which has obviously been harder in the last year, is that I like to move around. I like the stimulation of going to a library or a cafe. I find changing my environment a tremendous stimulus for creativity.

Tim Harford

Maxine:

I think there is something really lovely, too, in revisiting something you’ve already researched. It doesn’t always have to be about a new thing; I think there is something really nice in moving away from the throwaway culture of today where everything has to be new which is challenging in its own right.

Tim:

It’s an interesting question as to whether we are moving away from that throwaway culture. A lot depends on the medium that we use. Clearly there is something very hasty about TikTok and Twitter. Thinking about Netflix, I was just watching – and this isn’t high art – a spin off TV series of a Marvel movie and I realised the characters get so much space and complexity and you can focus on the backstory in much more detail; on-demand programmes can be much more complex than an old school TV series. In a 1980s or 90s TV series you just couldn’t guarantee that you could catch up if you missed something. But now, people will watch when they’re ready and watch in order, so you can make plotlines a lot more complex. Podcasting is similar: with on-demand and long form you can be sure that people will listen to your work as intended.

Maxine:

Your books are very accessible and readable. I’m curious: is that something you’ve had to cultivate, or is it something that comes naturally to you?

Tim:

I don’t think readability ever comes naturally to people; you have to work at it. Steven Pinker has a very nice concept called The Curse of Knowledge which explores what happens when you want to know something, whether it's terribly sophisticated or very simple, and you use a term you assume everybody knows. For example I might refer to someone as ‘he,’ but the person I’m talking to might not know who I mean by ‘he.’ And this knowledge affects any communication. When you’re trying to convey information to somebody, the point is that they don’t know what you know. It’s very hard to imagine and to put yourself in a position as someone who doesn’t know what you know. This applies to all communication, in particular when the medium doesn’t have capacity for ideas and feedback; if you’re a listener in a conversation you can say, ‘excuse me, who?’ In a book, there’s no way for the reader to say they don’t understand a word you’re using. So it takes clarity, rewriting and effort; no, it doesn’t come naturally to me but I really admire books that are easy to read whilst being complex, sophisticated and challenging.

Maxine:

Is there anything you need to work well, whether it’s an environment or a schedule or something else?

Tim:

I think it helps to have a schedule, like anything else, but that doesn’t guarantee you always get what you want. My book writing is constantly being interrupted by everything else. Today I got an email from a producer asking me to send something by noon, so at some stage I’ll have to set the mic up and submit it. We’re constantly being interrupted. One thing I find useful, which has obviously been harder in the last year, is that I like to move around. I like the stimulation of going to a library or a cafe. I find changing my environment a tremendous stimulus for creativity. That little bit of extra distraction in an environment is hard to put my finger on, but I’m sure a lot of people will recognise this sentiment.

Maxine:

Are you somebody who, when reading and struggling to find connection, will still finish the book or will you stop and move on?

Tim:

I hardly ever finish a book. Unless it’s fiction, and even then I often don’t finish fiction. With fiction you’re getting more from the second half than you are from the first half. But with most non-fiction you get more from the first half than the last and if the book you stop reading means you pick up another one I don’t feel that bad not reading books to the end.

Maxine:

In the intro to The Undercover Economist you make the point that no-one in the world could make a cappuccino, in its entirety. It took a whole host of suppliers, makers, sellers, engineers, machinery etc. to create everything needed for that drink to be in existence. It strikes me that businesses are like this, too. I’m curious, how can people who are making decisions in business – such as launching new projects or products into the world, changing the focus of their company and pivoting – how can these people stay open minded but not gullible, be guided but not blinkered by data?

Tim:

One of the cardinal virtues I describe in my new book is curiosity: just being interested in how things work, asking questions. I think people in business want to have a certain curiosity about what the business looks like from different angles. When you’re working with your designer, what else do they see? If you’re serving customers, what does this whole thing look like from the point of view of the customer who’s never heard of your product? Someone who has never heard of your service? What does it feel like to apply for a job in this company? What is the culture like? Work to see things from a different angle. What are other companies doing? What can I learn from what my direct competitors are doing? What can I learn from companies in totally different industries or sectors? What do they take for granted? Some views may seem quite radical, but getting out and about and talking to people to see things from all perspectives is likely to make you less gullible.

Maxine:

There’s often much pouring over data to make a decision within organisations, whether that be a rebrand, product launch or otherwise.. But, despite all the preparation and effort in making a decision, there’s always a difference in thinking about a decision and then the reality of a decision. For example, Gap did a very, very short lived, infamous rebrand in 2010 that lasted six days before they rolled back. But decisions, especially in large organisations, are hardly ever taken lightly. In newest bestseller How to Make the World Add Up you mention the concept of bird’s eye and worm’s eye view; could you explain this?

Tim:

We all know about the bird’s eye view; the worm’s eye view is up close, seeing things in perfect detail. It’s a term that Nobel prize-winning economists now use, along with the creators of microfinance. The point I make in the book is that you really need to have both. The bird is a long way away and gives you the big picture, whereas the worm’s eye view lets you see things up close. In many ways you get the bird’s eye view from the data and the worm’s eye view from personal experience – and you need both. Because I’m a bit of a geek, people assume that I would always say ‘trust the data.’ And in some circumstances, yes, it should be trusted because there are certain kinds of questions that only data can answer. For example, questions such as what kind of drugs most effectively treat patients with severe COVID. An individual can’t answer that for you; you need solid statistics. But at the same time there are lots of questions that statistics can’t answer and you need personal conversations to inform, those much richer and more vivid experiences. And the challenge I was setting in the book was to use both, which sometimes takes you in an unexpected and interesting way.

Maxine:

I think it’s so interesting, because industry is so reliant on analysis. I’m curious whether there’s something different for leaders who are not necessarily at the coalface; whether they can have a kind of wishful thinking when not in a ‘doing role,’ especially when technology is constantly changing the way that we interact with businesses and the way that businesses operate?

Tim:

Yes, there’s a phrase that the economist Friedrich Hayek used: “the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place.” There is a lot going on in a particular place at a particular time that people need to react to. If you’re stuck in your boardroom with your PowerPoint slides and your spreadsheet graphs it’s easy to have the illusion that you see what’s going on. But, of course, those graphs are already old. I do think you need to get out and about and see what’s happening. I was talking to the US military about this.

One of the most interesting people I’ve ever interviewed was HR McMaster, who was very influential in reshaping US strategy in Iraq. From a relatively junior position he was in charge of around 7,000 troops. A lot of what he did was trying to understand, in tremendous detail, what was going on, how the US Army could be more trusted and how it needed to change its behaviour. And this was encouraged from the top – but a lot of this was done by middle management because they could actually see what was happening on the ground. McMaster told me that you can think you can get situational awareness from sitting behind a computer screen, but you can’t. All your radar, your satellites, they’re fantastic – but ultimately for the kind of work you’re there to do, counter insurgency work, you have to actually be there. Talking to people. Looking them in the eye. Shaking their hands. We’re not all running counter insurgency units but approaches like these are very widely valid; senior management need to understand what is actually happening. They need to understand what’s happening when a customer visits a store, how they are greeted, how their needs are met. It’s very easy to lose sight of that.

Maxine:

After listening to your Cautionary Tales podcast about the serial killer Harold Shipman I was really shocked, silenced really. What I took away from the podcast is when you look at data you can find answers – like the fact that it could have been possible to uncover Shipman’s crimes a lot sooner if you looked at certain data points. I was struck by your questioning of what’s lurking in the things we’re not looking at and not interrogating? Is the answer more data, or something else?

Tim:

The Shipman story is really important, and shocking. There’s a challenge of understanding what he did and the harm he caused and the human suffering. Whilst, at the same time, understanding that there is a method you can use to figure out in food production if you have enough chocolate chips in your cookies – this same method could have spotted Shipman. I try and hold these two things in mind – the power of data and the human element.

I got an email yesterday from someone whose parent was murdered by Shipman. She wrote to me about what it was like to listen to the podcast and she was happy with what we had done, and grateful for the story we told, and that the story had been done justice. This is a reminder that these things are not abstract. We’re dealing with human suffering and, in the case of Shipman, real evil being done. Nevertheless a spreadsheet could have caught him, with the right sort of analysis – and not complicated analysis. It’s a reminder to not lose sight of the power of data to tell us things we’re missing, but at the same time to recognise that data misses things, too.

Maxine:

It feels like more open data can only be a good thing. In Scotland, a company called Spire who specialise in satellite technology in space are doing a thing where they’re opening up their space data with other researchers and non-profit organisations, for them to interrogate and use. And this is a really interesting way for them to share what they have, especially with universities. I was wondering if this is something more organisations may do, to open up their data, which will then allow others to choose where to look and what data to interrogate?

Tim:

Yes. The challenge, of course, is getting the right data in the right format in a way that makes sense and retains privacy. There have been some interesting examples in the last year with two projects in Oxford. One is called OpenSafely with the NHS. It’s a data platform that allows researchers to send questions in code, sensitive statistical analysis, into this data warehouse that contains 17 million GPs records of NHS patients. 17 million health records have the potential for tremendous violation of health privacy. The way that OpenSafely works is that you don’t ever see the data: you write your question in code, you submit the code, and you get the analysis back. But the data stays in the warehouse. At the same time, the process of writing and running code is automatically shared with every other user, so the analysis is incredibly transparent and collaborative but the data stays private – which seems like alchemy to me.

Another example is with COVID, and the RECOVERY Trial [a national clinical trial aiming to identify treatments that are beneficial for people hospitalised with COVID]. I was speaking to the team at RECOVERY who shared that every single time a patient enters intensive care with COVID, the doctors aren’t exactly sure what to do. So, we have to systemise the tossing of the coin; there’s a treatment, it might work or it might not. Or, we know it works but we don’t know if it’s best to give it to them for three days or seven days. The RECOVERY Trial basically automates these procedures so a doctor can take their iPad to the patient’s bedside, take the details of that patient and be given the correct instruction: give the patient this medicine, but don’t give them that medicine. The system has no administrative load on the staff but it generates an enormous amount of information and has saved many lives. It’s not so much a case of ‘what data do we need?’ It’s: what structure do we need to generate the right kind of data, in a simple way and in the right moment, which is tremendously powerful.

Maxine:

That’s really interesting, it sounds like it’s trying to create a best case procedure based on a person’s particulars. It reminds me of the book The Checklist by the American doctor Atul Gawande. It highlights the need for checklists to save lives in heavily procedure based industries like aviation and medicine – both jobs where you are often working with new people for the first time each day.

Tim:

Funnily enough I just sorted through my bookshelves. I finished writing one book and now I’m thinking of writing something else and saw The Checklist sitting there, unread, and so I pulled it to the front and it’s the next book to be read – so funny you should mention it. Gawande’s writing is fantastic.

Maxine:

As a final thought…

In How To Make The World Add Up you mention visiting China with your family, and you mention an overwhelming sense of the scale of the place and a fear that someone in the family could get lost. I was working in Beijing and, on arriving at the office from the airport, I accidentally left my suitcase in a taxi. I ran after the taxi to no avail, watching it drive off into the distance. Every rational and logical thought I had suggested there was no way I was seeing my suitcase again, lost in Beijing. But, I had a receipt and thanks to some help from local colleagues who contacted the company, they managed to manually track down the driver – by contacting drivers one by one – and miraculously, I got my bag back. If I had been logical about it I wouldn’t have even tried to track it down. It seemed futile but with help from others, I did.

Tim:

It’s amazing how kind people can be and the efforts that they go to.